Fun

Table of Contents

- Intro

- What is Fun?

- Moral lessons from Fun

- What Fun is not

- Pleasurable emotions ≠ Fun

- Pleasurable activities ≠ Fun

- Other open questions with the Fun Criterion

- Playfulness

- Evolution

- Beyond the Fun Criterion

- Agency-first

- Long-term consequences

- Following pleasure

- Outro

Intro

The Fun Criterion (FC) is a concept introduced by David Deutsch and discussed by him across various podcasts[1]. It holds that the absence of Fun is a warning sign. If we aren't having Fun while doing an activity, it suggests something is going wrong. In that case, we should consider whether to adjust our approach or abandon the activity altogether.

The FC is a powerful tool for understanding the mind and avoiding coercion. But it is also prone to misinterpretation, which can carry risks. So far, most accounts of the FC have left its definitions and boundaries somewhat vague and open, which can make those risks harder to address. Out of a strong personal interest in understanding the FC—and having encountered many of these ambiguities myself—I have gathered the various perspectives and attempted to define its boundaries more clearly in this essay. I also explore what the FC is not, and how it can be supplemented with other moral heuristics.

What is Fun?

In the original YouTube video on the FC: "What is the "Fun Criterion", David Deutsch describes Fun in a particular sense: a state of unobstructed problem-solving. It is the opposite of thwarted problem-solving — when some part of your mind is being suppressed, ignored, or overruled without considering its content.

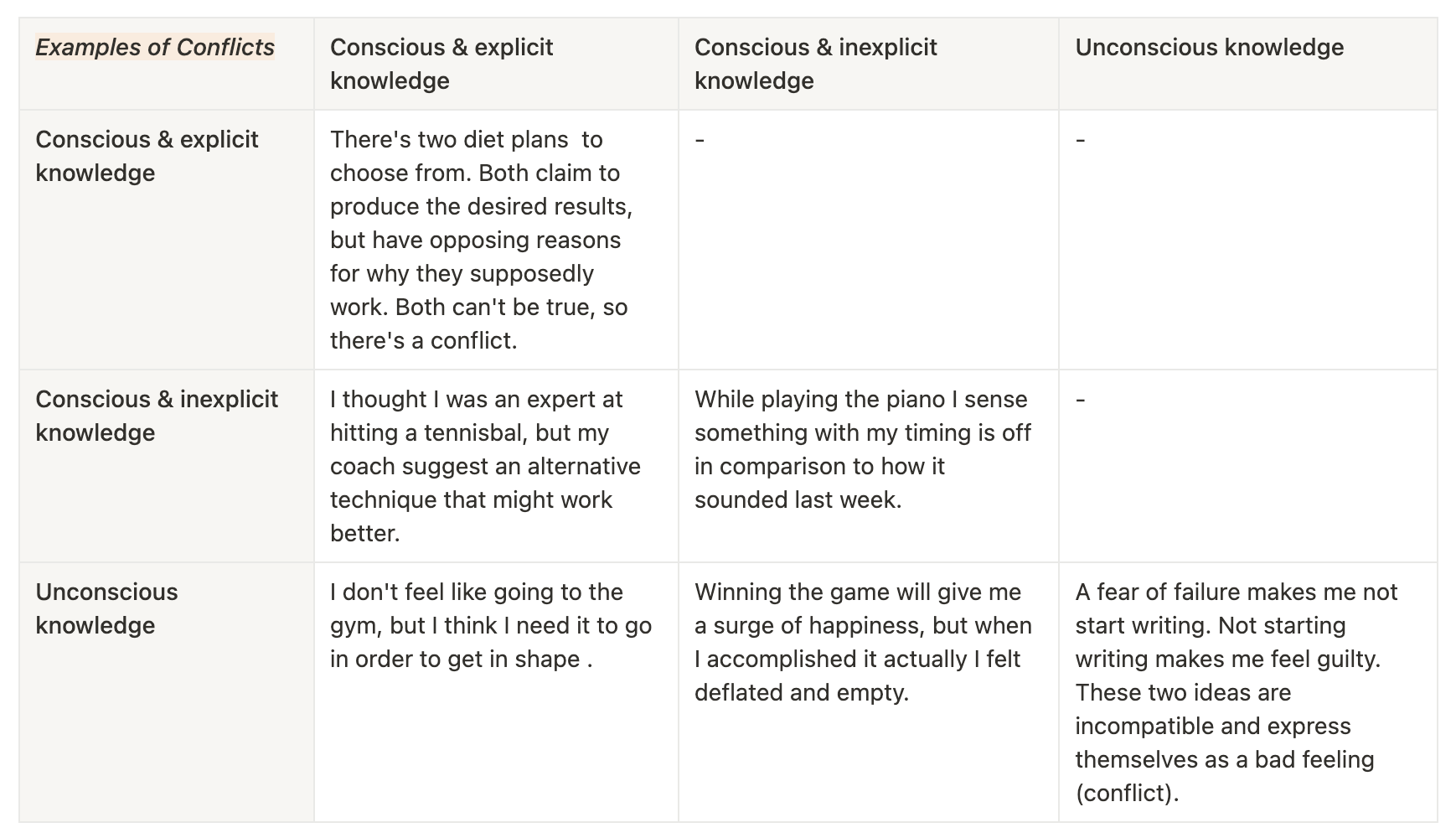

We reach the state of Fun when we take seriously all the knowledge which is currently active in our mind. David Deutsch distinguishes three types of knowledge (which we also call ideas):

- Conscious explicit knowledge – ideas we can fully or almost fully express in words, such as plans, goals, values, and stated opinions. Because they are expressable, they are easy to examine, criticize, and communicate.

- Conscious inexplicit knowledge – know-how we can use but cannot fully articulate in words, such as motor skills, habits, or a sense of rhythm. We can work with these directly by training or practice, even if we can't verbalize them.

- Unconscious knowledge – ingrained instincts, drives, and biases that influence us indirectly, often through feelings such as hunger, fear, or unease. As David Deutsch puts it, unconscious knowledge “affects you via your feelings, it affects you via your mood, it affects you via things that can’t be easily stated in words, but they can be felt.’’ We cannot directly access the unconscious; instead, we must infer the underlying knowledge from the feelings it produces. Importantly, feelings themselves are not knowledge, nor are they proof that unconscious knowledge is at play—explicit and inexplicit knowledge can generate feelings too.

At any moment, several ideas from these different types may be active in our mind.

When they conflict — when two or more have incompatible expectations, explanations, or aims — we face a problem (I made a video exploring various types of conflicts here and have listed a table below:).

Problems are normal. Problems are ever-present, and all life is problem-solving, as Popper first noted and Deutsch regularly emphasizes. Being hungry, not understanding an instruction, or even choosing what to wear are all examples of problems. The only time things go wrong is when we try to get rid of the problem by thwarting one part of the mind, instead of addressing the underlying conflict. Thwarting is coercion in action. It obstructs our natural problem solving. It happens when we are forced by ourselves, or others, to shut down an idea without taking it seriously — for example:

- Ignoring emotional signals and nudging ourselves to “just push through”

- Overruling explicit reasoning because “I should trust my gut”

- Dismissing doubt or discomfort without considering if what produced this feeling was valid

We can notice when we are being thwarted by turning our attention to what's happening in the mind, but we can also feel the result of the thwarting. Examples include: muscle tension when suppressing emotions, guilt when ignoring explicit moral knowledge, or a nagging "this isn't right" feeling when your boss tells you to open a presentation with a bad joke. Fun is the absence of thwarting. It is the state in which all active ideas are taken seriously, and allowed to conflict with each other. If our minds are not coerced, we are having Fun.

David Deutsch emphasizes that the FC is about noticing the absence of thwarting — checking whether we are having Fun, not predicting if something will be Fun. (He also notes that "mode of criticism" would therefore be a more accurate term, but Fun "Criterion" has remained the common term.)

‘Fun criterion’ sounds as though you can kind of evaluate in advance what’s going to be fun. […] I think it’s more accurate to say that [lack of] fun is a mode of criticism rather than a criterion. [I]f something seems to be not fun, that is prima facie a criticism of it. If something you are doing, or propose to do, isn’t fun, then there’s something unsolved there, it’s something that has to be answered.

David Deutsch, Reason Is Fun Podcast, episode 1, ‘What is “fun”? What is suffering?’, youtube.com

A final nuance about the state of Fun is that taking all types of knowledge seriously does not mean acting on or satisfying every one of them[2]. To take something seriously is simply to pause and consider it—to notice a conflict and ask what lies behind it. It does not mean we must fix all conflicts, or rid ourselves of every negative emotion. Since all knowledge is fallible, some of it will inevitably be mistaken. In the cases that the knowledge behind a sensation is in error, nothing needs changing—we can let the sensation be.

For example, when we take a feeling of fear seriously it means asking what knowledge produced it. Perhaps we believe public speaking is dangerous because we were bullied in the past. If we examine that belief and find it unwarranted, we can recognize the error and move ahead despite the fear. Sometimes the feeling fades quickly after such a realization; other times it lingers. That persistence is normal—the signals usually diminish with time as the error is repeatedly acknowledged. As long as you are taking the signals seriously and not suppressing them, you will still be in a state of Fun. You will only leave Fun if you suppress it.

Moral lessons from Fun

Fun is good, and coercion is bad. Coercion is unpleasant, immoral, irrational, and ineffective. From this, we can draw some practical moral lessons:

- Avoid external coercion. External coercion occurs when someone authoritatively limits our freedom without consent, disregarding what part of our mind wants. Examples include traditional schooling, hostile work environments and authoritative parenting styles. Avoid environments where coercion is prevalent.

- Avoid self-coercion. We often suppress parts of our mind without realizing it: ignoring pain signals, or pushing aside doubts in favor of "the plan." The reverse also happens—we follow our gut or trust our heart while dismissing explicit reasoning that points another way. The remedy is to regularly check for signs of self-coercion, notice them, and take seriously whatever arises in your mind. This isn't always easy—self-coercion is often subtle, entrenched, and disguised as "normal." We may even adopt coercive thought patterns as defaults. When we believe we "just have to do certain things," we chronically obstruct our own problem-solving. Such suppression builds unhappiness and suffering into everyday life, making it harder to address the underlying issue. In those moments, it may help to first shift into a better headspace—going for a run, making tea, talking with a friend—so that you regain the clarity needed for honest self-inquiry, instead of diving headfirst into the tangle.

- Make it Fun. Many activities can be approached in different ways. If something requires coercion to get through, find a way to make it Fun. Change the context by doing it with different people. Make a game or competition out of it. Or just find a different way to do the thing.

- Maximize Fun over time. A good life is one where most waking hours are spent in Fun. Therefore we can evaluate environments, responsibilities and activities by whether they improve our “Fun balance” over the day.

What Fun is not

So far, I've explained the heart of the Fun Criterion (FC): the desirable state of unobstructed problem solving, and its mode of criticism—the lack of fun—that signals an undesirable state. This part of the FC is solid and relatively uncontroversial. Now, we'll begin to discuss aspects that are more ambiguous. One question at the center of this is: what don't we mean by Fun? In my view, fun cannot be felt directly, and therefore any interpretation of the FC as "doing what feels fun" is a mistake.

Although David Deutsch is not entirely explicit on this point—as we'll see later—I believe he supports this view and likewise does not regard Fun as a feeling either. As discussed earlier, we can recognize the lack of Fun (thwarting) through our feelings. This raises a natural question: can we directly feel Fun itself? In this interview with Dwarkesh Patel Deutsch states that Fun is not an emotion. That's clear — but could we still recognize Fun through a set of positive emotions? Maybe enjoyment, excitement, or joy reliably signal Fun? Unfortunately not. We can be in Fun while experiencing all sorts of feelings: pain, strain, calm, fear, joy, or even neutrality. Think of the last miles of a marathon that hurt, wrestling with a difficult bug in code, the nervousness of basejumping, or the stillness of meditating. Each can be Fun, despite very different emotional experiences. Deutsch emphasizes this point in the aforementioned interview as well as this tweet.

The key takeaway I derive from this is that you cannot reliably identify Fun through your feelings. What you can reliably feel is when you are not having Fun — the sensations that accompany thwarting. When you feel thwarted, you know you are in coercion and therefore not in Fun. When that is absent, you are in Fun.

This distinction is important to acknowledge because in everyday language "doing what's fun" means pursuing activities that are enjoyable. In the case of the FC, Fun refers to the unobstructed state of problem-solving, free from coercion. Advice like "follow the fun" changes meaning entirely depending on which sense of fun is intended. David Deutsch has occasionally described Fun in ways that resemble the everyday sense — for instance, saying in an interview with Naval Ravikant that "following the fun" is what Borlaug, Faraday, and Newton did, or (as we'll see in an example later on) hinting that some chess moves are more fun than others. These are rare and loose expressions rather than substantive inaccuracies. In my view, his intended meaning remains Fun as a mode of thinking, not a feeling or property of an activity.

I draw a sharp distinction between Fun and enjoyment because blindly pursuing enjoyment can be risky and even harmful. Moreover, If we treat enjoyment as conducive to Fun, the idea would contradict itself: it would mean trusting one signal above all others, instead of taking all knowledge seriously. To show why this matters, I'll outline two common misinterpretations of "following enjoyment" and the errors they contain:

Pleasurable emotions ≠ Fun

One misinterpretation is to treat “follow the fun” as “do whatever feels good in the moment.” This reduces decision-making to a search for pleasurable experiences.

It is true that pleasure (positive emotions) are often a byproduct of solving a problem or making progress toward one, however it is too error prone to blindly follow. For starters, we often pursue pleasures to avoid taking our problems seriously: drinking after a breakup, binge-eating to mask sadness, playing games to procrastinate on meaningful work. This shows that we can be experiencing pleasure while thwarting other parts of our minds. In those cases you're enjoying yourself, but not having fun.

Secondly, and more importantly, emotions are not a type of knowledge — they are downstream of knowledge. Emotions are signals produced by all three types of knowledge to convey something to our conscious awareness. They can signal if there is a problem that needs addressing, or provide feedback on how a particular problem-solving activity is progressing

Judging actions solely by the emotions they produce ignores whether the underlying ideas that caused them are correct and valid. A stance echoed by David Deutsch as well:

Deciding ‘I should do whatever pleases me most’ [when determining what sort of life to want] would give you very little clue, because what pleases you depends on your moral judgement of what constitutes a good life, not vice versa. [I]f I ask you for advice about what objectives to pursue in life, it is no good telling me to do what […] I prefer, because I don’t know what I prefer to do until I have decided what sort of life I want to lead or how I should want the world to be.

David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity, chapter 5, books.apple.com

The correct approach is therefore to take these emotions seriously by considering what upstream knowledge may be causing them, and for what purpose. Focussing on the content of the ideas rather than what emotions they produce.

Pleasurable activities ≠ Fun

A second misinterpretation is to treat “follow the fun” as “prioritize activities you enjoy.” While there is some truth in this — we should focus more on activities we enjoy than those we don’t — the idea is naive and incomplete. It assumes that certain activities reliably produce positive emotions, but it isn't so simple. Context matters. A walk with friends may be enjoyable, while the same walk with someone you dislike may be miserable.

In addition, our preferences are not fixed. As David Deutsch has said in this podcast; human preferences are just ideas that are subject to criticism and change, unlike the relatively fixed preferences of animals.

Treating activities as inherently pleasurable encourages following or avoidance without examining the current content of our preferences and the surrounding context. This, again, can create coercion: you might push yourself into something because you “usually enjoy it” while suppressing a current, relevant objection from another part of your mind. For example, forcing yourself to go for a walk you don’t actually feel like taking, simply because you usually find it pleasurable, is not Fun.

If we remember that Fun is defined by the absence of thwarting, not by the presence of pleasure, we avoid both of these traps. Pleasurable emotions and activities can be part of Fun — but only when all active knowledge is being taken seriously and nothing is being suppressed.

Dennis Hackethal, in his article “Fun Criterion vs Whim Worship” explores these risks further and highlights why conflating Fun with feelings can be dangerous.

Other open questions with the Fun Criterion

So far, we've covered the relatively uncontested view that Fun is a state of unobstructed problem-solving, and the more debated—but, in my view, correct—interpretation that Fun cannot be identified by a set of enjoyable emotions.

Now we arrive at two further nuances, often raised in discussions of the Fun Criterion, whose meaning is less clear. Even David Deutsch has said he cannot precisely define all nuances of Fun. Some aspects remain ambiguous, and in the next section I’ll highlight two such open questions that I hope we will understand better over time.

Proxies for Fun: play, curiosity and interest

In some conversations, David Deutsch has described doing what’s Fun as something akin to playfulness: following one’s curiosity or rebelling against one's explicit knowledge. In one particular episode of the The Reason is Fun podcast he talks about a chess master making a playful move (I cleaned up the transcript. This isn't 100% accurate):

He often says things like, “I’m tempted to play this move. I know I shouldn’t… no, I can’t resist, I’m going to play it.” In the Fun Criterion video, I described fun as when your explicit and inexplicit ideas align. Here, his explicit ideas as a commentator say, “Don’t do it,” but his inexplicit ideas want to play the move because it’s fun. This isn’t necessarily a contradiction — his explicit ideas as a commentator are about what’s most likely to lead to a win, but fun is harder to verbalize. Sometimes he chooses fun even if it’s less likely to win. Chess forces you to integrate explicit and inexplicit theories — unless you’re a chess engine, which only has explicit theories and can’t have fun. Engines occasionally produce “fun” games, but only by accident, not by aiming for it. When playing voluntarily for enjoyment, you’re integrating explicit and inexplicit ideas. In chessplayer “Ginger GM” his case, part of the fun is raising possibilities that seem to lead to a beautiful game, even if he can’t calculate all variations.

David Deutsch, Reason Is Fun Podcast, episode 1, ‘What is “fun”? What is suffering?’, youtube.com

I’m not entirely sure how to interpret this. It could simply be another way of describing the state of taking all parts of the mind seriously—neither ignoring intuitions nor dismissing unconventional ideas.

It may also point to something else: a particular set of emotions that act as proxies for whether something will lead you into the state of Fun. Note that there is seemingly an inconsistency here, because as we saw earlier, Deutsch has also said that the Fun Criterion isn’t about predicting whether something will be Fun, but rather about whether something currently lacks fun. This is why I choose the word proxy rather than signal or criterion. A proxy is an observable correlate that reliably accompanies the state of Fun, but it is not a requirement in the criterion sense. We can be in the state of Fun without these emotions, and we don’t yet have a clear understanding of the causal mechanism tying those emotions to Fun—so proxy seems most appropriate.

I’m open to accepting this nuance of “following play, curiosity, or interest” into the broader theory of Fun. But I would caution against calling that “following the Fun.” If we conflate Fun with specific emotions, we run into the same notion of blindly following emotions—and thereby risk thwarting our problem-solving.

I hope David will shed more light on this in the future.

Thank you to Dirk Meulenbelt for raising this question and discussing it at length with me

The role of Evolution and alignment

The final few sentences of the original Fun Criterion video puzzle me: (again, I cleaned up the transcript, this is not 100% accurate).

It’s not enough to simply recognize that there’s a problem. You must create new knowledge—especially when unconscious or inexplicit theories conflict with explicit ones.

How do you solve problems if you can’t translate the theories into the same “language”—explicit, inexplicit, or unconscious? And how do you know when you’ve succeeded? This requires unconscious conjecture, inexplicit conjecture, and explicit conjecture—as well as criticism in all those domains. So how do you cross the boundary between these areas of knowledge, when translation may be difficult—or even impossible in practice? The answer is: all these processes are forms of evolution. They are a collection of ideas evolving in an environment. In biology, the environment consists largely of other genes. In the mind, however, there are many kinds of ideas. They aren’t directly translatable, but they still evolve in the environment of one another. When things are going well, conjecture and criticism are happening in each area—explicit, inexplicit, unconscious—while taking into account what the others are doing, or at least what they are.

A simple example: when you make explicit criticisms of your explicit ideas, you don’t just check whether they’re logical, consistent, or whether they solve the problem. You also notice: “Do I still feel the unpleasant feeling that signals the conflict (i.e. nameless dread)?” That becomes part of the criticism. The same is true at the inexplicit and unconscious levels. These domains can’t directly translate into each other, but they still influence one another through evolution. Explicit ideas can directly confront each other through logic and experiment, but more broadly, all ideas affect each other by evolving together.

Ideally, you want to reach a state of mind where all these kinds of ideas—explicit, inexplicit, unconscious—are influencing one another. And when that’s happening, you’re having fun.

David Deutsch, What is the 'Fun Criterion'? (David Deutsch – behind the scenes), youtube.com

It makes sense that all parts of the mind should be allowed to influence one another, and that they must all be acknowledged and taken seriously—preventing that would amount to coercion. But Deutsch seems to go further: he suggests that fun encourages (or even requires) these parts to actively interact. His reasoning appears to be that there are multiple modes of creativity (conjecture and criticism), and that fun arises when they are all engaged. That’s an interesting notion, but I still see the core as simply acknowledging and accounting for all the types of knowledge currently in play, not necessarily requiring each to participate or deliberately seeking them out. Perhaps he means something different and I'm missing something.

In another podcast, Deutsch says the Fun Criterion is about aligning thinking processes. My interpretation is that he means aligning the process of “taking seriously all types of knowledge approaches,” rather than forcing ideas themselves into alignment. When we do take all knowledge types seriously in a given moment and then choose a solution, that choice reshapes the composition of ideas in our mind (across all three types). This in turn produces new sensations and feelings that feed into the next iteration of problem solving. I suspect this is what Deutsch has in mind when he says that ideas affect one another through evolution [3].

Beyond the Fun Criterion

So far, we've covered what the Fun Criterion is—unobstructed problem-solving—and what it isn't—the pursuit of pleasure. We've also touched on what's less clear: its relation to playfulness and evolution. From this, we can draw sharper boundaries—inferring what the Fun Criterion does not directly address, and where it falls short.

Many people, myself included, once treated the Fun Criterion as a complete moral compass: something that could guide both how to do things and what to do. And while it's highly effective for the how — ensuring we work without coercion — it offers little guidance for what to do in the first place.

The Fun Criterion doesn’t urge us to take initiative, accept responsibility, act economically, or decide when to face the unknown. If we exclusively follow the moral lessons from the FC outlined above, we will only minimize coercion in our local problem-space, without ever exploring different opportunities. Used in isolation, it can keep us comfortable and rational, but stagnant.

That's why I think it's worth identifying heuristics that complement the Fun Criterion while staying true to being unobstructed as well as aligning with the epistemology of Critical Rationalism.

Agency-first

There is no shortage of powerful lessons and guidelines that we can derive from both the Fun Criterion and David Deutsch's improvements upon Critical Rationalism:

The Fun Criterion

- Take all parts of the mind seriously and avoid coercion.

- Try to make activities Fun.

Critical Rationalism

- All evils are due to a lack of knowledge.

- Problems are inevitable and solutions create new problems which must be solved in their turn.

- All transformations that do not violate the laws of physics are soluble by creativity.

- Human creativity is universal and allows us to understand everything.

- Preserving the means of error correction is more important than fixing any particular error.

But, for these lessons to matter, they must be enacted. Ideas left in our heads don’t change the world. Projects in notebooks produce no results. Insights without action achieve nothing.

That’s why I see agency—the consistent, proactive application of oneself—as a principle that even precedes the Fun Criterion. Only by expressing and enacting our ideas do we expose them to feedback and allow them to evolve.

Expressing ideas allows them to be criticized and improved. Enacting them—living by them—tests their usefulness and validity. This process refines not only our worldview but also our interests and values. We discover what engages us, what contexts suit us, and which principles work best. Action is the fuel of creativity and progress. More important than perfect planning or analysis is simply moving forward. If you’re unsure what to do, start by doing. At worst, you’ll learn what doesn’t work; at best, you’ll uncover new directions and preferences. Don’t overthink. Don’t overanalyze. Just start solving problems and apply what you learn.

Engaging with the world is often more transformative than endless self-analysis. Many "internal" issues are more effectively solved through external action in the real world. Social anxiety shifts by participating in groups. Self-doubt weakens through achievement. Fear of rejection dissolves by risking rejection and surviving it. Action allows our knowledge to evolve: each action creates feedback, reshaping what we know and the problems we face. Pure introspection rarely does this; it recycles old ideas and stays theoretical. At its worst, it traps us in victimhood — an endless search for excuses instead of focusing on solving our problems.

Tying this back to Fun: without agency, the FC risks being misapplied. One might focus only on "how can I make my present situation more fun?" and avoid any step that feels risky or uncomfortable. That leads to optimizing for local fun—a loop of overthinking, planning, or self-analysis—rather than pursuing global fun, which requires playfulness, experimentation, and error correction in reality. Local fun can be riddled with self-coercive thought patterns that masquerade as caution or preparation, but it is just fear keeping us from total engagement with the world. The ultimate spirit of Fun is not avoiding discomfort, but discovering new possibilities through proactive creative action.

Long-term consequences

The Fun Criterion allows us to check whether we are in a state of Fun right now. Because Fun is always assessed in the present, it cannot tell us whether we will be in Fun later. For that reason, it does not, by default, factor in long-term outcomes — yet many of life's most rewarding experiences require balancing both immediate and delayed consequences. That balancing is something we must add ourselves.

This is not an argument for "suffer now for Fun later," which wrongly treats coercion as a necessary evil. Rather, when making decisions, we can consider both short- and long-term effects on Fun. For example, you might decide to attend a seminar that some parts of your mind initially question, but which, after fair deliberation, you judge will give you valuable skills to live more unobstructed in the future. This isn't coercion because your concerns aren't suppressed — they're acknowledged, addressed, and found to be outweighed by the anticipated benefits.

Adopting responsibility for something over the long run is another example of why factoring in long-term consequences matters. In logotherapy, Viktor Frankl emphasized that meaning arises from committing ourselves to a responsibility — whether it’s for a project, a person, or an ideal. This sense of responsibility changes how we relate to challenges in day life: difficulties become part of fulfilling a commitment rather than obstacles to avoid.

This doesn’t mean such a life is always free from coercion or always Fun. But it does show how a deeply held responsibility — one that isn't resisted by the mind — can reduce the weight of short-term frustrations. Minor setbacks lose their sting when they serve a responsibility we’ve chosen, and our attention shifts from momentary discomforts to the larger aim we’re working toward.

Long-term responsibilities don't just help us persist in the moment — they also shape our overall frame of mind. Responsibility and a larger aim create a context in which we are more often in the state of Fun. Without major responsibilities, we would slip in and out of Fun more frequently, since we would constantly need to reassess our preferences and face decisions.

Intentional constraints to enhance productivity

At first glance, constraints such as deadlines might seem counterproductive. A FC purist could argue that imposing them risks coercion by suppressing parts of the mind. But when applied intentionally, constraints can support creativity and productivity.

Setting clear boundaries can make us take a project seriously. By deciding in advance what we will work on and when, we give it our full, undivided attention, which often makes us more efficient. This stands in contrast to open-endedness without structure — “I’ll do it when I feel like it” — which easily invites indecision and idleness.

There is of course a danger with intentional constraints, namely that we become inflexible. Thankfully, The Fun Criterion offers a safeguard: if a competing thought grips our attention, we can take it seriously, note it down to revisit later. Or, if genuine interest shifts in our mind, we can acknowledge that and adjust rather than forcing ourselves through. Boundaries work best when they are firm enough to focus our attention, yet flexible enough to adjust when new knowledge emerges.

Following pleasure

I've argued that simply "following pleasure" or "following pleasurable activities" is not in the spirit of the Fun Criterion and can lead to coercion. To be clear, I still don't think following pleasure should be considered part of the Fun Criterion, but let's take another look and see if, with tact and care, it can be a useful supplement to Fun.

Before we continue, it’s worth restating the main problem with the following emotions: they are downstream of knowledge. Chasing the effects while ignoring the causes is irrational and often leads to thwarting problem-solving. So, in discussing the pursuit of positive emotions and the avoidance of negative ones, we should limit ourselves to activities whose underlying reasons we examine and judge to be sound and worth acting on.

Pleasant emotions in the moment

From a Critical Rationalist perspective, there’s nothing wrong with allowing people to freely follow their own reasons and interests — including those that are accompanied by pleasant emotions. If we would instead forcibly interject and preemptively set restrictions on what to do or not to do, then we'd be coercing and hence doing more damage then if we simply let creativity run its course.

Aaron Stupple and Logan Chipkin, authors of The Sovereign Child, illustrate this with what they call the "Greedy Child Fallacy" — the mistaken belief that if a child were free to do as they pleased, they would for the rest of time exclusively indulge in ice cream and television and other forms of instant gratification. In reality, children — like adults — are sovereign individuals who, in the absence of coercion, tend to explore, adjust their preferences, and self-regulate far more effectively than when constrained by arbitrary rules.

For example, a child given unrestricted freedom to choose their meals might initially gravitate toward sweets and snacks. But over time, curiosity, bodily feedback, and a natural desire for variety often leads them to experiment with other foods, just as adults eventually tire of comfort food and seek something more nourishing. The absence of imposed rules allows the process of learning itself to guide better choices.

The difficulty is that most of us live under layers of coercion, rules, and norms — whether we realize it or not. For people whose minds are regularly (self)coerced, absolute freedom to “just follow pleasure” can easily turn into escapism from coercion. For example, someone stuck in an unfulfilling job might spend all their free time binge-watching shows or playing games, not because these activities are their deepest interest, but because they offer quick relief from a coercive environment. While the real cause here is the coercion in their lives — not the urge to escape it — a pragmatic approach might be to pair the pursuit of pleasure with other heuristics such as: regularly examining our preferences, cultivating awareness of coercion and setting intentional constraints.

Maximizing overall pleasurable activities in life

If maximizing Fun (the same as minimizing coercion) each day is a good maxim, what about maximizing pleasurable emotions? Should we try to pack in as many emotional highs as possible — and avoid the lows? Let’s explore if this balancing exercise has potential.

First, we must recall a couple of earlier points. Activities have both short- and long-term consequences. Some feel great now but come with a steep cost later; others are difficult in the moment but yield lasting satisfaction. Also, whether an activity is enjoyable depends on our current preferences and context — so when we talk about its "emotional experience," we're making an approximate guess based on how it typically feels.

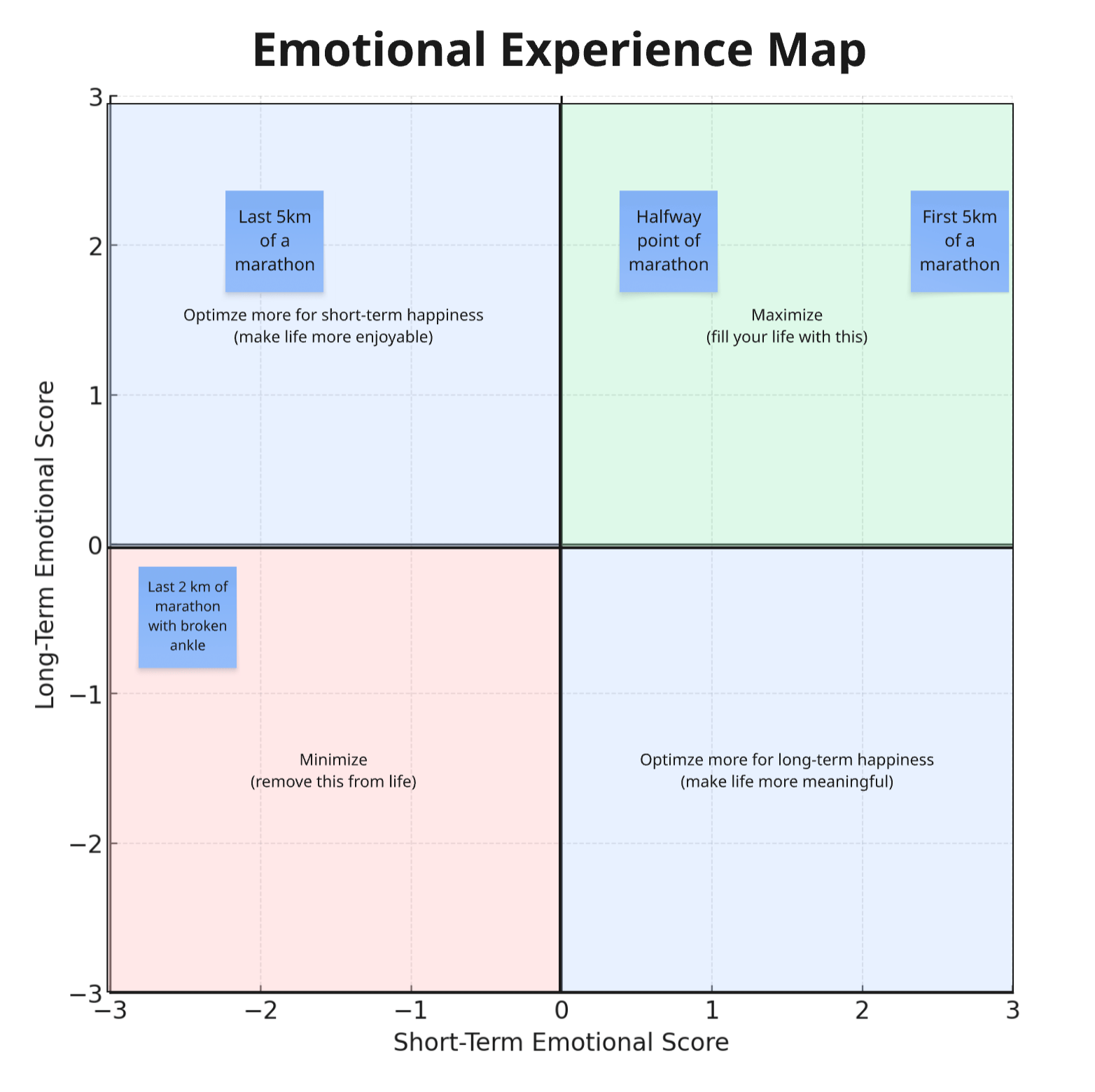

With that groundwork in place, we can begin the mental exercise of plotting our day-to-day activities, aiming to adjust toward more positive emotions and fewer negative ones. To make this tangible, I’ve created an Emotional Experience Map with example ‘post-its’—for instance, consider running a marathon: if you suffer in the last 5k but know it will bring long-term happiness, push through; but if you break your ankle near the finish, forcing yourself onward will cause far more harm than stopping and sitting it out.

Here, the x-axis represents short-term emotional score; the y-axis represents long-term emotional score. By plotting activities and estimating their short- and long-term effects, you get a picture of where your current distribution lies. The actual scores aren’t important — the focus is on which quadrant they fall into and how they compare relative to each other.

Once you have your distribution, you can decide whether to adjust the concentration of activities in each quadrant. For example:

- Bottom-left: remove as much as possible.

- Top-left: if this dominates, it might be healthy to add more immediately enjoyable activities

- Bottom-right: if this is overrepresented, consider adding more responsibility or meaningful projects

- Top-right: prioritize these — they’re high-value.

In my view, when people say "Follow the fun" or "Do what you love" what they're really pointing to is the importance of maximizing the top-right quadrant. They don't mean you should do things you only value in the long run (top-left), nor do they mean chasing instant gratification (bottom-right). Interpreted this way, I think it's good advice, granted that unobstructed Fun is prioritized first.

This conceptual Emotional Experience Map can be a useful tool for creating a more enjoyable life — but it's not a replacement for the Fun Criterion. Fun is about unobstructed problem-solving, not pleasant feelings. This exercise can certainly complement the Fun Criterion by helping you spot patterns and trends in your emotional life, but the deeper work is still taking all your knowledge seriously. Without that, even a life full of "enjoyable" activities could still be plagued by coercion — and therefore, ultimately, be irrational and harmful.

Outro

This essay grew out of a series of conversations on the Fun Criterion. While there are many interpretations, I noticed there wasn’t a clear attempt to demarcate what it does — and doesn’t — mean. My aim has been to clarify its core, explore its open questions, and offer heuristics that might supplement it in practice.

I’m grateful to Bart Vanderhaegen, Dennis Hackethal, Dirk Meulenbelt, Arya, Darren Wiebe, Logan Chipkin, Aaron Stupple, Paul Raymond-Robichaud, and John (apologies for any omissions) for the fun exchanges that helped shape these ideas.

A special thanks to David Deutsch and Lulie Tanett for actively sharing these valuable insights and discussing them in various forums. I appreciate any time they discuss Fun and am eagerly awaiting new podcasts or essays on the topic.

If you want to stay up to date on new ideas emerging from Critical Rationalist philosophy — including theories, books and explainer videos — I highly recommend following and supporting the Conjecture Institute.

If you have any questions, criticisms or remarks please reach out to me on X

[1]: Podcasts where the Fun Criterion is extensively discussed:

- What is the 'Fun Criterion'? (David Deutsch – behind the scenes) https://youtu.be/idvGlr0aT3c?si=JfRb5kjrTW5fNnuW

- David Deutsch on The Fun Criterion, Objective Beauty & Artificial Intelligence: https://youtu.be/uQ2GHzFYxaI?si=hkVT1Ctv7z0ynekX

- David Deutsch - AI, America, Fun, & Bayes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EVwjofV5TgU&t=2s

- What is 'fun'? What is suffering? | Reason Is Fun Podcast #1: https://youtu.be/5e2LWxaqQUQ?si=e92eiwLa087SIH2X

- AGI with David Deutsch | Reason Is Fun Podcast #-1: https://youtu.be/jQnoxhoWhXE?si=tSKIq5forzOZ8JBJ

[2]: The pursuit of a life without problems or negative feelings is the pursuit of the unproblematic state — also known as death. This is very different from Fun, where the aim is to have an endless supply of interesting problems to engage with and solve in an unthwarted way.

[3]: This emphasis on evolution echoes Dennis Hackethal’s neo-Darwinian theory of mind, which suggests that ideas imperfectly self-replicate; thereby giving rise to the evolutionary process of human creativity.

Comments

Loading comments...